Epistolary novels, books in which the story is told through letters or other artifacts supposedly generated by the characters, have been around for centuries. Dracula, The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, and The Woman in White are all examples of classic epistolary novels (Doogan). However, in the past decade or two, the rise of the internet age has allowed this genre to expand in an exciting new direction. As social media accounts and online social connections become more common in the real world, they’re also cropping up in books, with some authors endeavoring to tell entire stories through social media transcripts and other online artefacts. But what kinds of stories are out there, and why is their use of social media so significant?

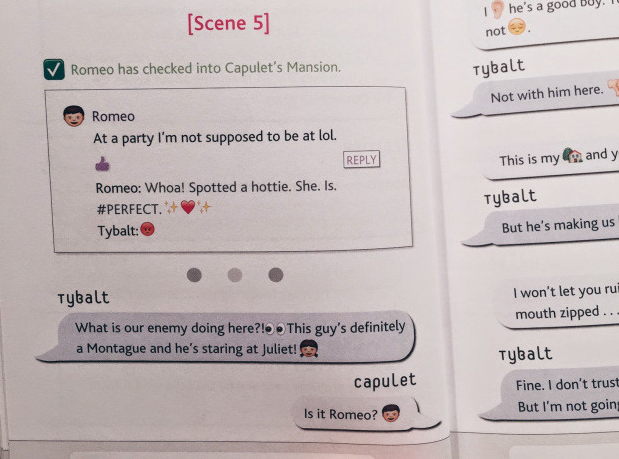

Perhaps the most ambitious ‘digital epistolary’ novel I’ve ever read is Gena/Finn by Hannah Moskowitz and Kat Helgeson. This book tells the story of two women involved in the online fandom for a buddy cop show who develop an intimate bond through the internet. Although the plot itself left me disappointed (mainly due to rampant queerbaiting and a bizarre shift in the second half), the format of the book was fascinating: the entire story is told through Tumblr posts (including fan fics), instant messages, emails, texts, and other online media. A similar approach is taken in Jenny Fran Davis’ Everything Must Go, the story of a preppy teen who follows her crush to a very liberal boarding school, although Davis incorporates letters and pen-and-paper journal entries as well as digital communications. Finally, the Internet Girls series by Lauren Myracle provides a unique case study because it includes four books published between 2004 and 2014, and Myracle updates the technology used by her protagonists to reflect the changing times.

What makes books like these three examples so fascinating? Firstly, they give you immense insight into corners of the internet you may have never visited yourself. For example, the fan community in Gena/Finn (which is fairly explicitly based on the real-life fandom surrounding the show Supernatural) provides a detailed rendering of all the positive and negative aspects of online fandom, from fans mutually supporting each other and creative pursuits like fan fic and fan art to polarizing disputes about popular ships and the harassment of actors. Additionally, by allowing you to see the same characters interact on different platforms throughout the book, it demonstrates how people tailor their communication styles to different circumstances while maintaining an identifiable personality. Everything Must Go stretches this exploration of modern role shifting even farther by showing the main character’s writing in her journals, a private medium, and online, a medium which is public to varying degrees. Internet Girls, which follows three friends through high school and the first year of college, explores how real-life friends harness digital platforms to develop their friendships and communicate things that might be harder to express out loud.

In addition to providing insight into different aspects of the internet, digital epistolary novels serve another important purpose: preserving a record of internet history. There’s plenty of scholarly work documenting the evolution of the internet and social media, but it’s not easy for journal articles to capture the feeling of being an internet citizen in a certain year in a clear and evocative way. Novels are the perfect medium to fulfill this purpose. Since Gena/Finn and Everything Must Go are both fairly recent, Internet Girls is currently the strongest example of digital epistolary novels as cultural records. The 2004 debut novel, ttyl, consists exclusively of IM transcripts and is full of the outmoded ‘chat speak’ of the early 2000s. In contrast, the most recent novel, yolo, incorporates platforms like Twitter and Facebook and is written according to a more contemporary style of online communication (although the title itself already places yolo as a book published in 2014 and not the current year). Particularly with current predictions that Tumblr is on its way out (Fingas), it’s easy to imagine that the online fandom scene will undergo major changes in the coming years. How valuable (or at least fun and nostalgic) might it be to revisit Gena/Finn after that shift occurs and explore a preserved model of fandom culture? Similarly, the protagonist of Everything Must Go uses the internet to engage with fashion in various ways. Picking up that book in a couple years could cue the realization that the norms around fashion blogging have undergone a significant shift. In essence, well-executed epistolary novels are like fossil records for the internet–and ones that are much more engaging and plot-driven than the actual fossil records available through sites like the Wayback Machine.

In conclusion, though I’m always down to read a classic letter-style epistolary novel, I’m incredibly excited to check out more social media-based books as they become increasingly common in the coming years. Finally, there’s a format to simultaneously satisfy my interests in reading and social media theory.

Sources:

Doogan, Jesse. “100 Must-Read Epistolary Novels from the Past and Present.” Book Riot. Riot New Media, 24 Aug. 2017, https://bookriot.com/2016/08/24/100-epistolary-novels-from-the-past-and-present/. Accessed 30 Nov. 2017.

Fingas, Jon. “Tumblr founder and CEO David Karp resigns.” Engadget. Oath Tech Network, 27 Nov. 2017, https://www.engadget.com/2017/11/27/tumblr-founder-david-karp-resigns/. Accessed 30 Nov. 2017.